Is Being Called a Decision Maker a Compliment? Four Ways to ensure that it is

As a leader, decisiveness is critical. Wallow in indecision, and your competitors eat your lunch, or your team abandons you. Great leaders are typically great decision-makers. The late Colin Powell stated that leadership takes place between 40% and 70% of the available information. When decisions are needed, if less than 40% of the information necessary to make the decision is available, it's nothing more than a wild guess. If 70% or more of the data is accessible, you've waited too long, and anyone can make that decision. Our success is defined by a history of good choices made within this narrow window when it comes down to it.

So, how can being called a good decision maker be a bad thing?

To begin to understand this double-edged sword, let’s draw some distinctions.

Decision Maker vs. Problem Solver – At face value, the difference between a decision-maker and a problem solver is semantics, but a deeper dive differentiates the two.

The problem-solver has a process that they go through when making a decision. They take an analytical approach. It could be as simple as listing and weighing the pros and cons of each choice. Regardless, there is a conscious level of thought, and their analytical approach and thought process can be taught to others. Problem solvers are more likely to engage others in the decision-making process, not only promoting collaboration but making it more likely that their colleagues will put more thought into a problem before coming to them for a decision. Unfortunately, this group is more likely not to decide at all.

Decision-makers, on the other hand, tend to lead with their gut and are quick to choose and respond. Their knowledge and instinct may lead to excellent decisions, but they lack process and don't encourage collaboration. As a result, their colleagues learn to come to them with problems and an expectation that the decision-maker will give them the answer. Decision-makers tend to be risk-takers, which coincides with higher stress tolerance. That means that they will keep making decisions as long as someone keeps bringing them problems. They can handle it.

With our population segregated in two, diving deeper explains where things can go awry.

Reactive vs. Proactive – The business lifecycle tends to be finite. The sequel to the Jim Collins book "Good to Great" could be called "Great to Gone." When a business launches, founders have no choice but to look out and up at the possibilities or "what it can be." They make proactive decisions about what they will do, who they serve, and how they differentiate. With this vision, sound strategy, luck, and perseverance, there will be clients to serve, proposals to write, calls and e-mails to respond to, etc., and the view shifts downward to "what it is." In other words, they become reactive. Growth slows, and if left unchecked, the business slides down the backside of the lifecycle curve.

The speed of business is accelerating, compounding the lifecycle problem described above. We have multiple means of instantaneous communication to tend to, and expectations for response time have increased. We've all received the call on our mobile asking if we got the e-mail sent fifteen minutes before. Even in smaller organizations, the pure volume of reactive decisions becomes all-consuming, and leaders play all defense and no offense, making it extremely difficult to win.

It's no surprise that the decision-makers tend to get caught in this reactive trap more than the problem-solvers. And, although forward movement is stifled, decisive, reactive decision-makers are recognized for their decision-making performance based on volume and frequency.

How to be a good decision-maker – Solving this puzzle may be the secret sauce to success. Here are four ways to be a better decision-maker.

- Balance problem solving and decision making – At this point, you've probably self-assessed who you are and the advantages and disadvantages. Liken this to the left (analytical/logical) vs. right (creative/emotional) brain comparison. When people balance both and operate with the "whole brain,” they are more effective. There are times when quick decisions are needed. There are other times when the team can be involved in the decision process or empowered to decide. The magnitude and timing of decisions will dictate, but varying your approach or assigning decisions to different team members will keep the organization moving forward while empowering the team and enhancing its collective skillset.

- Mindset shift – Any business where human effort is perceived as the key revenue generator carries a mindset that more complicated is better or has to be hard to be good. We glorify the person who worked 2,200 charge hours, and the likes of Elon Musk, who brag about eighteen-hour days and minimal sleep, further this mindset. Without getting into the debate of whether this is appropriate in this stage in the evolution of public accounting, the reactive decision-maker may liken themselves to a superhero, deflecting the constant attack from the villain's bullets with the perpetual swing of their shields. And it feels good to be busy and needed! When it comes to decision-making, it's critical to shift to a mindset that slow is smooth and smooth is fast. Not every decision warrants our attention, and one impactful decision is worth several that merely keep things at bay. It doesn't have to be hard to be good.

- Reduce the volume of reactive decisions – With a fresh mindset and a balanced approach, be aware of the type of decisions you are making. Keep a score of how many are reactive and how many are proactive. Which merely keep things moving and which move the needle forward. If we want better results, we need different behavior, and that begins with awareness. How many times do people walk into your office (physical or virtual), drop their problem on your desk, and walk out with the answer? A powerful way to focus on reducing the reactive decisions you are making is by taking a sabbatical. Ask yourself what processes would you put in place if you were going to take two months off? What are the delegation protocols while you're gone? What situation triggers the absolute last resort of calling you? Can't take one? Take a hypothetical sabbatical and go through the same process.

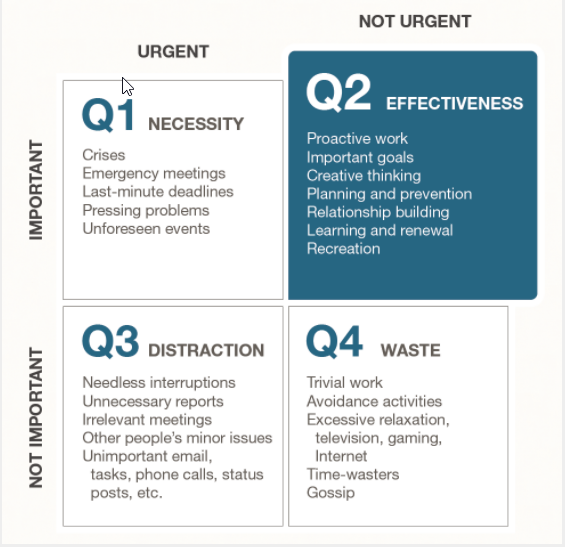

- Dedicate time to focus on proactive decision-making – Last but absolutely not least, carve out time to focus on the proactive decisions that drive personal and business growth. Review the Stephen Covey time management matrix and find a way to get in Q2 to focus on the important but not urgent things that will move you forward (by the way, client service falls squarely in Q1). Do whatever it takes to get there. Put it on your calendar. Join a peer group. Hire a coach. Go for a drive or walk. Take the scenic route home. Some people rely on a place or space to get them there. Author of the E-Myth, Michael Gerber, speaks about a dreaming room – a dedicated space for forward-thinking. A client of mine has a conference table in his office and a separate conference room attached to his office; one is for tactical work, and the other is for strategic planning and vision. Find what works for you, but create the time to do this.

The Conclusion?

Good decision-making is something that sets leaders apart. While there is no perfect mix of decision-making characteristics or a one-size-fits-all approach, focusing on the behaviors above will improve the likelihood of positively differentiating your leadership skills.

Interested in discussing this more with me? Schedule a call.